« Ils sont rentrés chez eux »: the political dimensions of displacement and ‘spontaneous return’ in Faradje, northeast DRC

Jolien Tegenbos, Thijs Van Laer, Jean Claude Malitano,

Bruce Ndenga Lotsna, Tasile Ruako

Congo Research Briefs| Issue 4

INTRODUCTION

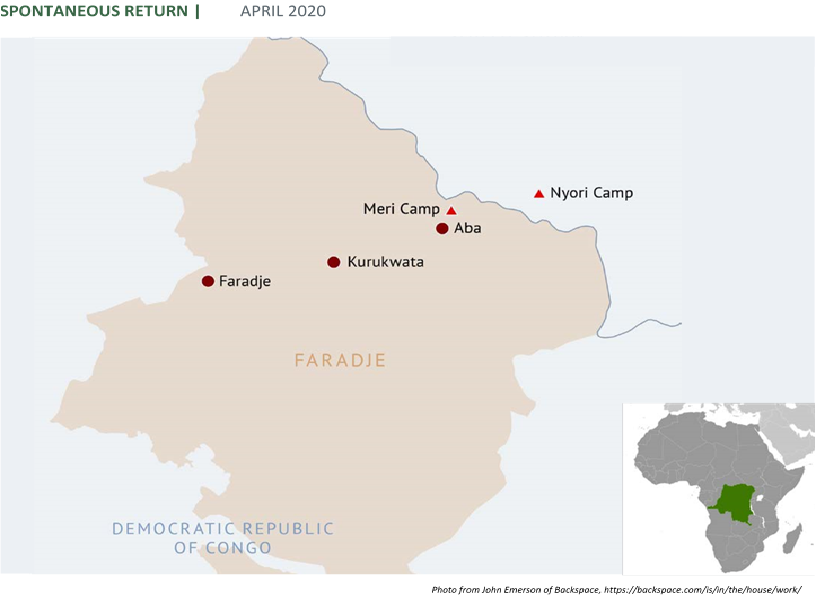

Scholars have only recently started to address repatriation and population return as an inherently political process. Influenced by growing criticism on socio-economic and aid-centric approaches, researchers have contributed to mostly top-down but also increasingly bottom-up analyses of ‘the politics of return’ (Tegenbos & Vlassenroot 2018: 19-21). To this day, we continue to have little understanding of the political impacts of population return in contexts of conflict and displacement, both from the perspective of countries of origin and (former) exile. This paper aims to contribute to this emerging debate on the political dimensions of return by focusing on the sudden ‘spontaneous’ return of 11,6001 Congolese refugees who were forced back from exile in South Sudan to their home areas in Faradje, in northeast DRC.

Clashes between government and opposition forces in the vicinity of Nyori Refugee Camp compromised the safety of many Congolese residents, forcing many of them to return home.2 In 2009, approximately 12,000 Congolese from Faradje territory had taken flight from the DRC to Nyori, in South Sudan’s Central Equatoria region, following violent attacks and atrocities committed by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA).3 This paper argues for the need to better understand the politics of return in contexts of continued displacement in light of changing (geographical) political configurations of power and authority that are embedded into broader realities of increased humanitarian presence and cross-border movements. In this way, the paper also demonstrates how people, institutions, and authorities impacted by and operating within contexts of displacement and return contest and negotiate authority as well as their positions on the ground.

The territory of Faradje lies in DRC’s Haut-Uélé province, formerly known as Province Orientale until 2015. The LRA crossed over from South(ern) Sudan and northern Uganda, where the origins of the movement lie, to northeast DRC in 2005.4 The LRA initially settled in Garamba National Park5 in 2005 but didn’t start carrying out attacks until December 2007 and, more severely, sparked off a series of violent attacks from Christmas eve 2008 onwards, notably in the territories of Dungu, Niangara, Faradje and Watsa (Durba), in the current Haut-Uélé province (then Province Orientale). Faradje was hit most severely in 2008-2009, most acutely following reprisal attacks conducted against civilians following “Operation Lightning Thunder,” a joint military operation between Uganda, southern

Sudan, DRC, and CAR, and backed by the United States (HRW 2009; Titeca & Costeur 2014).6 Abductions and violent attacks resulted in massive displacement across the region, emptying entire villages. In the years after mid-2010, this violence started decreasing as the LRA went into “survival mode” and gradually moved their activities to the Central African Republic and Sudan (Titeca 2019: 219). Respondents for this research criticized the inability of local authorities to protect civilians. Others noted instances in which the Congolese army arrived late and committed abuses against populations already under attack by the LRA.7

This paper focuses on the situation of returnees in the town of Aba, close to the South Sudanese border, and its surrounding chefferies (Logo Ogambi, Logo Lolia, Mondo Missa, Kakwa, Logo Bagela), complemented with insights from Faradje town and Kurukwata, all situated in the territory of Faradje. Most of the returnees in these areas had fled in 2009 to Nyori Refugee Camp in southern Sudan. Others had sought safety internally in DRC, in neighbouring Ituri province, or closer to home, in camps for internally displaced people (IDPs) in Aba, Djabir, Kurukwata, and Faradje, where many still reside today. Most of the internally displaced from Ituri province returned to larger towns in Faradje territory in 2010 when there was a perception of better security. This paper focuses specifically on refugee return, its political impact in Faradje and its profound embeddedness within a broader reality of (protracted) displacement and return of various populations, as well as in broader forms of cross-border and internal migration characterizing the borderlands between South Sudan and DRC.8 In the following sections, we will discuss the political impact of return in Aba and the broader territory of Faradje through three main, connecting themes: the politics of return; the politics of assistance; and changing political constellations. The first section will focus on the political failure of organizing official repatriation for Congolese before 2016 and its impact on returnees and political realities after return. The second section addresses the impact of the increased humanitarian presence and humanitarian structures of displacement on political dynamics in Faradje. The third and last section concentrates on how newly established political, humanitarian entities and spaces infringe on already existing forms of authority and legitimacy. Based on these three themes, we argue that the establishment of political/humanitarian structures during displacement have a continuous impact on the political situation in Faradje, and contribute to transforming issues of authority and legitimacy and changing political constellations.

This research brief is one of the outputs of a research project that focused on the political dimensions of refugee return in three key areas: Faradje (DRC’s Haut-Uélé Province), Kalehe (DRC’s South Kivu Province) and Burundi. The project “Returning to Stability” was funded by NWO-WOTRO and resulted in a report and interactive map based on two months of fieldwork in each of the research settings in 2019 by research teams based in the focus areas.9 For Faradje, we carried out a total of 57 interviews in addition to a number of field observations and documents gathered from humanitarian agencies, and the Congolese returnee and South Sudanese refugee committees. This paper is, therefore, a slightly adapted version of the Faradje case study in the report. All authors have participated to a greater or lesser extent in the fieldwork.

THE POLITICS OF RETURN

Discussions around a potential organized repatriation of Congolese refugees from Nyori preceded the eventual return of refugees to DRC in 2016. These discussions officially started in 2015 and involved local Congolese authorities, the DRC’s National Commission for Refugees (CNR), the South Sudanese Commission for Refugees (CRA) and UNHCR. In addition to sending a delegation in 2015 to visit the refugees in Nyori and gather information, potential sites were examined to settle landless returnees in Faradje.10 The preparations were put on hold in 2016 due to increased insecurity in South Sudan as the conflict between the government of South Sudan and the South Sudanese armed opposition escalated and spread to these Equatoria regions. This increased insecurity rendered repatriation logistically difficult. Insecurity in South Sudan in the form of violent attacks and increased penetration of armed actors in the camp directly reduced the safety of the refugees in Nyori. When the refugees eventually fled en masse back to DRC, Congolese authorities found themselves unprepared to receive, assist, and register them. Furthermore, they were accompanied by some 34,000 South Sudanese refugees who had also fled the upsurge in violence in the zone where Nyori camp was situated.11

The absence of an official tripartite agreement (and of accompanying humanitarian assistance) was an issue much debated during interviews. Interviewees said they would have preferred to return in the framework of an agreement between UNHCR, the country of refugee origin (DRC), and the host country (South Sudan), because of its legal framework, but also for its links to assistance and an official transfer of responsibilities for the refugee returnees from the country of refuge to the country of origin.

An official of the CNR explained the relative disregard for returnees by saying that the legal vocabulary for displacement clearly distinguishes “repatriates who return to their country of origin through an official framework,” from “spontaneous repatriates who return on their own without any official measures.” The latter officially have no right to reintegration assistance.12 During field research, Congolese authorities and humanitarian actors recurrently used the phrase “ils sont rentrés chez eux” (they have returned home) to legitimate and justify their detachment towards the spontaneous repatriates under study.13 In Aba, the administrative, legal distinction between returnees whose repatriation is organized and those who repatriate spontaneously, translated itself into daily conversations (with returnees, Congolese authorities, humanitarians, CNR) as a distinction between “repatriates” (organized, right to assistance) and “returnees” (spontaneous, no right to assistance). The labeling of the population under study as “returnees” instead of “repatriates,” was in turn contested by the returnees themselves, who preferred to identify themselves as either “forced returnees” or “repatriates,” as a way of emphasizing what they claimed was their right to assistance and other forms of support from CNR and the humanitarian agencies.14 Frustration among returnees over the political failure in assisting the Congolese to repatriate was moreover aggravated by the fact that funding and humanitarian resources had been made available to accommodate South Sudanese refugees in Faradje’s newly established refugee site, Meri, as opposed to the Congolese returnees, many of whom had fled the same violence. The assistance received by returnees was very limited and depended much on returnees’ own lobbying at CNR and humanitarian agencies. Moreover, in 2017 the small number of food rations available for after the return were cut.15 The organization of repatriation was, not only challenged by the 2016 violence in South Sudan but also by the process through which refugees and authorities from the country of refuge and origin negotiated population return. Interviews with returnees and customary chiefs revealed that the context in which these negotiations took place as well as political dynamics and power struggles between the refugee leadership and South Sudanese camp authorities in Nyori complicated the return process.

Before the start of the more official discussions around organized return in 2015, Congolese state and customary authorities had visited Nyori on multiple occasions and were met with a welcome that was lukewarm at best, and often even hostile. Already in 2009, when the LRA was still carrying out violent attacks in the region, a customary chief of one of the chefferies around Aba traveled to South Sudan and requested that his constituencies return home. Current returnees who had met him at the time testified that the chief had lamented that he could not preside over an empty chefferie.16 His visit was met with outright rejection, and refugees chased him away. Current returnees interpreted the chief’s request as a way for him to further his political interests while downplaying the gravity of ongoing insecurity in the country.17 The chief himself thought he had taken a considerable risk in traveling to South Sudan, for which refugees had been ‘ungrateful.’18 As such, while all returnees lamented the lack of a tripartite agreement for repatriation, this example demonstrates that refugee participation and agency in deciding the “when” and “how” of return is equally important.

According to returnees, political dynamics and power struggles in Nyori between the refugee leadership and South Sudanese camp authorities also complicated the return process. Official visits to the refugees in 2012, by the governor of the then-Orientale Province (now Haut-Uélé, which includes Faradje), and the 2015 delegation (cf. supra) were used as illustrations of these political tensions. In the years preceding 2012 and in the course of the following years, the refugee leadership in Nyori wrote letters to Congolese authorities in DRC to request repatriation. However, according to former members of these successive refugee camp committees19 and a former CNR official, the camp authorities (i.e. CRA and UNHCR) wanted to keep refugees in South Sudan, “because of their economic interests linked with the refugee presence and incoming humanitarian resources.”20 To achieve that goal, the South Sudanese camp authorities had created a rift between Congolese refugees who preferred to remain in the camp and those who wanted to repatriate to DRC.21 In the course of this power struggle, the camp management suspended the elected refugee committee, who had supported repatriation, and replaced it with a committee that followed the management’s interests and advocated for a continuous stay in South Sudan. The committee appointed by the camp authorities eventually met with the governor of Orientale Province in 2012, and with the delegation of Congolese authorities and humanitarian officials in 2015.22 In their communications with the Congolese authorities during both events, the committee denied that refugees supported the idea of repatriation.23 UNHCR and Terre Sans Frontières (TSF) appeared to have no knowledge of the political dynamics that had influenced the reception of the Congolese authorities in Nyori.24

These dynamics related to the politics of return continued to have an influence, despite the ‘spontaneous’ return of most Congolese refugees. Interviewees said that the remaining refugee committee in South Sudan, which had resisted return and is supported by the CRA, continues to attempt to exert influence over the returnees (cf. section politics of assistance). Several returnees said that South Sudan still claims responsibility for returnees to host them as refugees, provide assistance, etc. – a claim which was even accepted as legitimate by a CNR official, who explained that the Congolese never formally repatriated.25

THE POLITICS OF ASSISTANCE

The growing presence of a humanitarian apparatus in Faradje has had a profound impact on political realities. In response to large-scale internal displacement following the LRA incursions, humanitarian agencies arrived in large numbers and established themselves in domains such as education, health, protection, SGBV, livelihoods, food provision, construction, etc. Local NGOs such as the Association Pour la Promotion Rurale (APRu) and international ones like Invisible Children, Danish Refugee Council (DRC), Lutheran World Federation (LWF), and UNHCR settled themselves in Aba and its surroundings, and in and around IDP camps which were rapidly being created. The humanitarian presence decreased somewhat in later years and became less diverse with the departure of certain NGOs. However, from 2016 onwards, it received a new impetus with the arrival of South Sudanese refugees and Congolese returnees and the creation of the Meri Refugee Site. CNR enlarged its office and staff deployment in Aba, and NGOs multiplied. While some organizations have left Faradje over the years, a good number of them still remain. Historical cycles of violence and insecurity both in DRC and in South(ern) Sudan have resulted in internal and crossborder displacement before. Nevertheless, the arrival of the LRA and consequent large population movements (both flight and return) brought a significant humanitarian presence that had never existed before in Faradje. While this presence of humanitarian actors has fluctuated over time (decreasing, increasing, changing in diversity), it has gradually become embedded in the political arena as a set of actors involved in the acquirement, management (including establishing socio-political entities such as returnee/refugee committees), decision-making, and distribution of humanitarian resources and public services.

This humanitarian apparatus occupies a new space of authority next to existing forms of state and customary authority. UNHCR and NGOs established themselves in domains of public service provision, of which some are traditionally the responsibility of state and customary authorities. In the aftermath of the LRA and during the return of displaced communities, (re)construction of private and public infrastructure as well as rebuilding people’s livelihoods proved difficult. While Haut-Uélé, including Faradje, already suffered from “a history of gradual economic, political and physical marginalization and degradation,” the LRA conflict further entrenched this process (Titeca 2019: 219, 230).

In Faradje, local inhabitants (including returnees) stated that they had limited confidence in local state and customary authorities to provide the necessary resources to respond to the challenges brought about by (the impact of) displacement (including the forced return of Congolese refugees). The presence of humanitarian organizations and their resources were therefore deemed very valuable by both local and displaced communities, as well as local Congolese authorities. This wide variety of socio-political entities soliciting for humanitarian resources produced a very dynamic political landscape in Faradje. There are many modes of interaction between these different forms of authority, humanitarian actors, and different communities, which at times proved complicated and fraught with conflicts and distrust. Two issues particularly complicated this relationship: participation in humanitarian decision-making and the uneven division of resources distributed to different categories of people impacted by displacement and return.

Local authorities, civil society actors, and committees representing returnees, refugees, and IDPs complained about their lack of participation in decisions that would impact their communities. A local authority in Aba, for example, explained how he had been invited by UNHCR and one of its implementing partners to the opening ceremony of a school established for returnees and other populations, without ever having been substantially included in the development of the project.26 Also, the aforementioned committees were frequently in conflict with humanitarian agencies and the CNR about their role in the management and implementation of assistance and resources (see below).

Further, the available resources that UNHCR and its implementing and operating partners were able to provide were not nearly sufficient to answer the needs of different communities. The unequal division of these resources to different categories of refugees, the “host population,” IDPs, and returnees, moreover, added to these tensions. While South Sudanese refugees were receiving food rations and NFI’s in the newly established Meri refugee site, Congolese returnees who had accompanied them during their flight from South Sudan were neglected due to their ‘spontaneous return’. While the category of “host population” in areas of refugee presence was entitled to 20% of the refugee response budget, local inhabitants and customary authorities said that they received very little of it. Humanitarian aid in the remaining IDP camps existed, though it was also limited.

The case of the establishment of Meri can be used here to illustrate the complex and fraught nature of political interactions between the different actors, authorities, and communities involved in the managing and soliciting of humanitarian resources.

The customary chief who had successfully solicited the established of the camp (and its humanitarian resources) in his chefferie quickly entered in conflict with locals and IDPs already living in the area. The settlement of South Sudanese refugees thus coincided with the displacement of the local (IDP) population who was simply told to move their homesteads and agricultural activities elsewhere. In response, the local communities later challenged the chief’s authority by reporting problems related to the refugee site, including about land and natural resources, to UNHCR instead of to him, despite his authority over such matters.27 The eagerness of the chief to solicit the refugee site’s presence in his chefferie without taking his population into account thus also resulted in decreasing the legitimacy of his authority in the eyes of his constituencies.

Meri also merits attention as an illustration of the entanglement between the politics of the South Sudanese refugee and Congolese returnee committees in their dealings with the CNR and humanitarian agencies. Several returnees interviewed for this project complained that they received little to no assistance, while refugees living in nearby Meri refugee site did receive such assistance. A returnee said: “We were not welcomed upon return. They only cared about the South Sudanese refugees and abandoned us.”28 Humanitarian actors confirmed such frustration, and said their attempts to explain it by pointing at the different legal status of returnees, compared to refugees or official repatriates, did not change the frustration.29 As such, many returnees explained to have limited confidence in their authorities to improve their situation: “they cannot do anything for us.”30 Interlocutors often said that the returnees understudy “sont rentrés chez eux” (have returned home), which would justify the Congolese authorities’ negligence towards them.31 As Congolese returnees felt ignored and disadvantaged compared to refugees, they tried to benefit from the assistance provided to refugees. An unconfirmed number of 1000 Congolese returnees were said to be secretly registered in the refugee settlement in order to secure a means of survival.32 Additionally, several hundred Congolese wives of South Sudanese refugees were registered on arrival as beneficiaries, but were later deactivated for cash distribution in October 2018.33 Open protest and clashes between South Sudanese (with silent backing from Congolese) and humanitarian actors ensued, resulting in injuries and intervention by security services and in a decision to cut cash support for the entire camp for four months. Previous existing frictions between the South Sudanese refugee committee and the camp authorities (CNR and humanitarian partners) over insufficient assistance were further compounded by these events. Following the clashes, the CNR replaced the elected refugee committee with a temporary one, and later commanded the imprisonment of the former committee members, banning them as well from upcoming committee elections. The Congolese returnee committee and local civil society supported the former South Sudanese refugee committee in their conflict with the camp authorities, as all of them had experienced their own frustrations with the interventions and working methods of the CNR and humanitarians. Civil society in Aba even demanded the removal of humanitarian staff and threatened to impose roadblocks.34

Meanwhile, the suspended refugee committee members

(and the civil society) returned the favor by backing the Congolese returnee committee whose conflict with TSF over a project providing cash assistance to a part of the returnee population escalated. When humanitarian assistance or livelihood projects for returnees were carried out, the limited number of beneficiaries and allegations of corruption further fueled frustration among returnees and friction with humanitarian and state authorities. The program providing cash assistance resulted in disagreements about the nature and beneficiaries of the project, and in tensions between the NGO involved and the committee of returnees. Both accused the other of not being open to dialogue and requested the removal of the other party. Only after mediation from the territory administrator was a temporary settlement found.35 A member of the returnee committee said that such problems impacted on their relations with authorities and their constituencies: “Unfortunately, our committee is not well perceived by humanitarians and state authorities, because every time we intervene in meetings with humanitarians, our recommendations and proposals are not taken into considerations. As a consequence, even our brothers, the spontaneous returnees, think that it is us, the committee, who block assistance.”36

Finally, the lack of humanitarian assistance for returnees also drew in the involvement of the camp authorities in Nyori. The returnees’ desperate need for resources prompted some of them to answer calls from the remaining refugee committee in Nyori camp to collect humanitarian assistance by traveling back to South Sudan. Some returnees went back to collect food and non-food (NFI) items on specially organized distributions of assistance for Congolese; others continued their schooling in Nyori while living in DRC or answered the recruitment calls for nurses in Nyori by preparing their departure. After one specially organized distribution of NFI’s in March 2018, South Sudanese combatants kidnapped a group of former refugees on their return to DRC. Military guarding the border closed it to prevent other incidents and refused to heed the request by the South Sudanese camp authorities and the president of the aforementioned refugee committee to reopen the border.37 This example equally illustrates how the South Sudanese camp authorities continue to exert their influence over the Congolese returnees who were never formally repatriated and who find themselves in desperate need of resources for survival.

CHANGING POLITICAL CONSTELLATIONS

The various forms of displacement in Faradje territory and the ensuing humanitarian presence also transformed existing political geographies and created new socio-political entities that encompass new forms of power and authority.

The establishment of new polities in the form of refugee and IDP camps has created new political geographies encompassing new forms of power and authority. In a context of displacement, camps bring about new population concentrations, forms of organization, leadership positions, and a mixture of opportunities and challenges for the communities already living in the area. In Faradje, the presence of IDPs or returned refugees in certain areas has increased while simultaneously leaving many villages empty as large groups of displaced people have not (yet) returned to their original homes. Due to their protracted nature, some of the IDP camps that continue to exist have managed to de facto elevate their rank to that of a locality with their leaders taking up responsibilities similar to that of a customary chief. In his chapter on justice and security provision in Haut-Uélé, Titeca explains how this often creates political tensions over authority both in the areas that people fled to (between the (new) chief of the displaced and the customary leader of the “host” area) and that they fled from (between the displaced chief and emerging forms of power in his area of origin) (Titeca 2019: 299).

Further, in the context of displacement, these new population concentrations also attracted humanitarian resources, including new infrastructure and assistance. Health centers, schools, and shelters were constructed where they had been destroyed in the areas from which people had come. This increased humanitarian presence also impacted the political landscape in Faradje. In the groupement of Djabir, for example, the majority of the population of approximately 11 villages had fled the LRA atrocities to another locality where many of them still reside today. Following their arrival, the chief of this locality then moved his residence closer to the NGO offices coming in to assist the displaced and struck deals with the chiefs of those communities to receive a percentage of the fees generally paid to the latter by their populations to mediate in conflicts. He oversaw the construction of schools and medical infrastructure by humanitarian agencies in his locality and received their financial support.38 Another customary chief managed to use the establishment of an IDP camp in his locality (and thus the increase of population, responsibilities, and humanitarian resources) to now present himself as the chief of a groupement, a more important political entity. In other sites, representatives of the displaced community have assumed roles similar to those of a customary chief.

Apart from enabling new political geographies, “conflict and displacement continuously create new combinations of power and authority” (Titeca 2019: 229). The humanitarian system operates through a different set of socio-political entities than state and customary authorities. Humanitarian structures of displacement gave way to a range of committees representing returnees, South Sudanese refugees, and IDPs. UNHCR and CNR facilitate the election of such representative structures of refugees and IDPs to ensure ‘beneficiary’ participation in refugee and IDP camp management issues. The returnee committee, however, was created by returnees in 2016 and consisted of former members of the successive refugee committees that had existed during exile in Nyori. Interestingly, the returnee committee was specifically created in order to secure representation towards the incoming NGOs and make claims to assistance. They wrote letters and had meetings with CNR and TSF, were involved in the registration process of returnees, and attempted to influence the distribution of humanitarian resources.

Such committees are well placed to employ their categorical statuses (of refugee, returnee, IDP) to claim assistance, rights, and recognition as ‘vulnerable parties in need of help.’ Yet, while such committees are important political actors to be reckoned with, their relatively low hierarchical status in the humanitarian structures also increases their vulnerability. The refugee committees for Congolese in Nyori and South Sudanese in Meri had both been suspended and replaced, respectively, after interests about repatriation and protests against the deactivation of assistance for Congolese wives of South Sudanese refugees. Also, the legitimacy and role of the returnee committee were called into question by TSF and UNHCR after tensions arose with humanitarian partners around a project for cash distribution to a group of returnees (cf. supra).

Further, such committees, at times, enter into competition with already existing authorities. Both want to be involved in negotiations over the distribution of assistance and other resources and claim representation of overlapping communities (e.g., residents of a locality of which many are also returnees). Such competition over authority also exists between customary and state authorities on the one hand and leadership positions that are remnants of refugee life in South Sudan, such as former camp and block leaders. Some Congolese had never been in leadership positions before they were elected as Nyori’s camp president, refugee committee members, or refugee block leaders. Displacement in this way also carried the potential of reconfiguring people’s place in society upon return from exile. Further, on the basis of their identification as a distinct category of ‘returnees,’ current representative committees and former refugee leaders exercise a form of (officially) apolitical agency in their relationship with the humanitarian system, which is different from the existing political roles exercised by customary and other local leaders. In practice, of course, both political and apolitical spaces infringe on each other and are significantly entangled.

CONCLUSION

This research brief has argued that the political/humanitarian structures that were established during displacement have a continuous impact on the political situation in Faradje, and contribute to transforming issues of authority and legitimacy and changing political constellations. Since the advent of the LRA atrocities, displacement has resulted in an increased humanitarian presence unprecedented in the history of Faradje. Although the humanitarian apparatus is officially apolitical, this paper demonstrated that it has a distinct impact on the political landscape.

The humanitarian apparatus produced new political geographies and socio-political entities that infringe on already existing political structures, at times resulting in conflict and friction between the two. Being able to claim, direct, distribute, and manage humanitarian resources has become a source of legitimacy and authority. As local authorities proved unable to support and integrate returnees and contribute to reconstruction, returnees and other population groups attempt to find a place into the same humanitarian structures that governed them during exile or that were established during displacement. Furthermore, the continuous influence exerted by South Sudanese camp authorities encourages returnees in desperate need of resources to find help and assistance in Nyori, which recurrently proved to be a dangerous enterprise. Dynamics concerning the lack of organization and assistance in the repatriation process continue to impact relationships between Congolese authorities, humanitarian actors, and returnees. Although the time-span of the research does not allow the authors to make conclusive arguments on how profoundly the negative experiences of these actors before, during and after the return process have impacted enduring processes of legitimacy and authority, it is clear that they still play a role in how these parties perceive each other(‘s actions). Certainly, the political impact of return in Faradje is as much connected to histories of exile and displacement as to the actual return and reintegration process that followed.

ENDNOTES

- The official statistics of registered returnees from South Sudan in December 2018 stands at 11,572. Interview with CNR official, Aba, 25 February 2019.

- For more information on the 2016 renewed upsurge in conflict, see among others: ACLED, 2016, ‘Country Report: South Sudan Conflict Update July 2016’; Réseau pour la réforme du secteur de sécurité et de justice, 2016, ‘Haut-Uélé: les réfugiés du Sudan du Sud d’Aba manquent de nourriture’.

- Interview with 3 members of the returnee committee, Aba, 20 March 2019.

- For discussions on why and in which political context the LRA relocated to northeast DRC, see for example Schomerus, The Lord’s Resistance Army in Sudan; Le Sage, “Countering the Lord’s Resistance Army in Central Africa”.

- Garamba National Park borders with South Sudan in the north and partly overlaps with the territories of Faradje in the east and with Dungu in the west.

- HRW, 2009, The Christmas massacres. LRA attacks on civilians in northern Congo; Kristof Titeca & Theophile Costeur, 2014, ‘An LRA for everyone: how different actors frame the Lord’s Resistance Army’, African Affairs, 114/454, 92-114.

- For a more profound analysis of the reaction of Congolese security forces towards the LRA and local populations, see: Titeca & Costeur, ‘An LRA for everyone’.

- For discussions on the broader histories of trade, (forced) migration and cultural linkages in the regional borderlands of northeast DRC, northwest Uganda and the Equatoria region in current South Sudan, see for example: Leopold, Inside West Nile; Omasombo, Haut-Uélé; Meagher, “The hidden economy”.

- See International Refugee Rights Initiative, Conflict Research Group, Actions Pour la Promotion Rurale, Groupe d’Etudes sur les Conflicts et la Sécurité (2019). Returning to Stability? Refugee Returns in the Great Lakes Region.

- Interview with Congolese informant, Aba 25 February and 25 March 2019. Officials who were involved in these pre-return discussions and who were contacted by the research team were generally hesitant to provide much information about the details and particularities of the process. Despite multiple requests, also UNHCR also did not share its version of this process. The apparent sensitivity of the topic was, due to time constraints, unfortunately not explored during field research. For this reason, also the extent to which South Sudanese authorities were involved in these discussions, is not clear.

- Interview with CNR official, Aba, 25 & 26 January 2019.

- Interview with CNR official, Aba, 28 March 2019; interview with head of CNR, Kinshasa, 15 August 2019.

- Interview with military official, Aba; Interview with returnees, Aba, 22 & 24 February 2019.

- Interview with 3 members of the returnee committee, Aba, 20 March 2019; interview with civil society, Aba, 20 March 2019.

- Important: returnees were provided with food assistance for the first time since it was cut in 2017 just after the fieldwork was concluded in May 2019.

- FGD with returnees, locality of Banga, 26 March 2019.

- Interview with returnees, Aba, 27 February 2019 and 26 March 2019, with NGO representative, Aru, 23 March 2019, and with customary leader, Kakwa-Ima, 25 March 2019.

- Interview with the chief of Kakwa-Ima, 3 March 2019;

Interview with Terre Sans Frontières (TSF), Aru, 23 March 2019; Focus Group Discussion with returnees from the chefferie KakwaIma, 26 March 2019.

- i.e. the refugee leadership, re-elected by camp inhabitants every few years under supervision of the CRA and UNHCR.

- Interviews with former CNR official, 25 February 2019; and with returnees, Aba, 22 & 23 February, 20 March 2019. Quote from 20 March. Actors in South Sudan were not contacted for this research however to verify these claims.

- According to several returnees, the main reason why many refugees had requested repatriation was the ever declining humanitarian assistance in the camp and thus aggravating living conditions. The increasing security in DRC was a factor too, though of a lesser extent. Refugees who had succeeded in establishing successful income-generating activities or those with criminal records back in DRC were said to prefer their stay in South Sudan.

- Authorities even briefly detained former committee members who were in support of repatriation when the governor of the then Province Orientale wanted to visit the camp in 2012. Interviews with returnees, Aba, 23 & 25 February 2019.

- Interview with 3 members of the returnee committee, Aba,

20 March 2019; Interview with Terre Sans Frontières (TSF), Aru,

23 March 2019; Interview with the chief of Kakwa-Ima, Aba,

25 March 2019; Interview with CNR official, 25 March 2019; Interview with returnees and customary chief, Banga, 26 March 2019.

24 Meeting with UNHCR and TSF, Aru, 21 June 2019. 25 Interview with CNR official, Aba, 28 March 2019; Interview with returnees, Aba, 26 March 2019.

- Conversation with local authority, Aba, 20 March 2019.

- Interview with local leader, Meri, 25 March 2019.

- Interview with returnee, Aba, 23 February 2019.

- Interviews with humanitarian actors, Aru, 23 March 2019 & Aba, 28 March 2019.

- Interview with returnees, 26 March 2019.

- Interview with military official, Aba; Interview with returnees, Aba, 22 & 24 February 2019.

- Reference to discourse governor province, 8 December 2018.

- The rest of the Congolese did not face suspension of their status as they had officially registered themselves as South Sudanese.

- Interview with CNR, Aba, 22 March 2019; Interviews with members of the former South Sudanese refugee committee on 24 February, 27 & 28 March; information from Congolese informants between 14-25 May, 10 June, July 2019.

- Interviews with civil society, Aba, 20 March 2019 and Kurukwata, 4 March 2019; with CNR, Aba, 21 March 2019; with NGO, Aru, 22 March 2019; and with returnees, Aba, 17 April 2019.

- Interview with returnee committee, Aba, 17 April 2019.

- Interviews with military and with returnees present during the incident, 26 March 2019.

- Conversations with Congolese informant, Arua, 18-20 June 2019.

REFERENCES

Human Rights Watch. 2009. The Christmas massacres. LRA attacks on civilians in northern Congo.

International Refugee Rights Initiative, Conflict Research Group, Actions Pour la Promotion Rurale, Groupe d’Etudes sur les Conflicts et la Sécurité (2019). Returning to Stability? Refugee Returns in the Great Lakes Region

Leopold, Mark. 2005. Inside West Nile: violence, history & representation on an African frontier. London: James Currey.

Le Sage, Andre. 2011. “Countering the Lord’s Resistance Army in Central Africa”, INSS Strategic Forum, 270.

Meagher, Kate. 1990. “The hidden economy: informal and parallel trade in Northwestern Uganda”, Review of African Political Economy, 17/47, 64-83.

Schomerus, Mareike. 2007. The Lord’s Resistance Army in Sudan: a history and overview. Geneva: Small Arms Survey

Tshonda, Jean Omasombo (ed.). 2011. Haut-Uélé: trésor touristique. Brussels: Le Cri.

Titeca, Kristof & Theophile Costeur. 2014. “An LRA for everyone: how different actors frame the Lord’s Resistance Army,” African Affairs, 114/454, 92-114.

Titeca, Kristof. 2019. “Public services at the edge of the state: justice ad conflict-resolution in Haut-Uélé” in: Kristof Titeca & Tom De Herdt (eds.), Negotiating public services in the Congo: state, society and governance, 214-234.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Congo research briefs are a joint publication of the Conflict Research Group (CRG) at Ghent University, the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) and its Understanding Violent Conflict programme, the Study Group on

Conflicts and Human Security (GEC-SH) at the University of Kivu Research Center (CERUKI), the University of Kinshasa (UNIKIN) and the Governance-in-Conflict Network (GiC). These provide concise and timely summaries of ongoing research on the Congo that is being undertaken by CRG, SSRC, GEC-SH, UNIKIN, GiC, and their partners.

Many thanks to professor Dr. Kristof Titeca and Dr. Naomi Pendle for their elaborate comments on the paper. This research brief is one of the outputs of the research project “Returning to Stability,” funded by NWO-WOTRO Science for Global Development. In this respect, the authors owe special thanks to the researchers and administrative staff of the organizations and research groups that provided crucial analytical input, logistical support, and orientation throughout the research process: Actions Pour la Promotion Rurale (APRu), International Refugee Rights Initiative (IRRI), Conflict Research Group (CRG), and Groupe d’Etudes sur les Conflits et la Sécurité Humaine (GEC-SH). Final credits to Sara Weschler for terrific language editing, as always.

This work was supported by the Partnership for Conflict, Crime & Security Research, a Global Challenges Research Fund collaboration of the Economic and Social Research Council; and the Arts and Humanities Research Council.